SQUAT CALABRIA

by Bill Weinberg, The Brooklyn Rail

The abandoned Hotel Centrale in downtown Cosenza, Italy, is a relic of ghastly 1970s-style retro-futuristic architecture, starkly at odds with the stately if decrepit medieval buildings of the city’s historic center, which begins just a few blocks away. But the Centrale has clearly been reclaimed by oppositional cultural forces.

The flag of Syria's revolutionary Kurds flies from the roof. A multiculti congregation of scruffy youth hang out in the lobby—some Italian kids with dyed hair and a punk aesthetic, some young migrants from Africa and the Middle East. A hand-scrawled sign at the entrance reads "Hotel Centrale Occupato"—with the O in occupato slashed with a lightning bolt, making the squatter symbol. Below, it reads, "Mangia, riposa... e lotta!" Eat, rest... and fight!

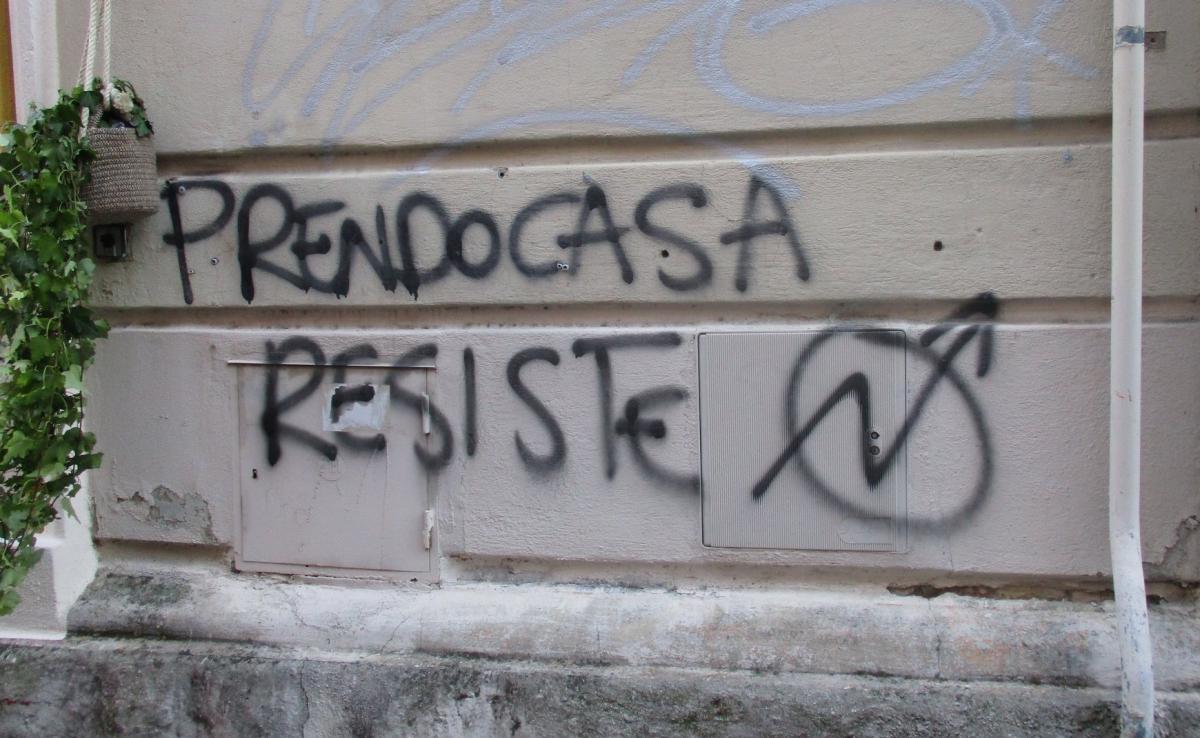

The Centrale is one of six buildings in the provincial city that are under occupation by the local squatter network, Prendocasa Cosenza—literally, Taking House Cosenza. The group began reclaiming abandoned properties around Cosenza in 2011, especially opening housing for the migrants and refugees that began entering Italy and Europe in large numbers around this time. In addition to the Centrale, still technically under private ownership, two of the properties are owned by the Catholic church and the remaining three by either the municipal government or the regional government of Calabria—in the extreme south of Italy’s mainland, the proverbial toe of the boot, a traditionally marginalized part of the country.

Some 300 people are living in these reclaimed properties, and only one squat has been evicted by the police since the movement was launched. The municipal and regional governments tolerate the squatters, and the municipality is actually paying the church for use of its buildings by the migrants and their activist allies.

It remains to be seen how long this arrangement will last, given the recent political changes in Italy. The country's far-right interior minister (and de facto ruler) Matteo Salvini was just removed from power in September as his coalition fractured and a new government was formed. But last November, he pushed through his draconian Decreto Salvini—explicitly aimed at two broadly overlapping groups: immigrants and squatters. In addition to restricting the rights of migrants and refugees to asylum and government aid, it imposes a five-year prison term for squatting.

The first squat eviction under the law sparked street-fighting in Turin, up at the other end of the country, in February. The squatters of Cosenza are waiting uneasily to see if Salvini's fall will be a reprieve for them.

Pride in 'Meticcia'

Across some overgrown train tracks from the Hotel Centrale is the Rialzo social center, in a squatted abandoned rail station. It was established in 2007 as a centro politico occupato autogestito (self-managed occupied political center, or CPOA), and brings together cultures of the many lands now disgorging their disenfranchised and usurped to Italy and Europe.

A part of the Rialzo has been established as a makeshift mosque for migrants from Muslim lands—the only mosque in Cosenza. In the spring, Rialzo hosted a Nowruz celebration in solidarity with the rebel Kurds of Syria's Rojava region. On the night I attended a squatter soirée there, a class in traditional West African drumming and dance was being led by a young teacher from Ivory Coast.

Some of the young Calabrese squatters at Rialzo recalled Salvini's past as leader of the Northern League, who rose to prominence in the ‘90s by stigmatizing Italy’s South as an economic drain. The Northern League actually sought secession from Italy for the industrialized Po Valley. Having dropped its separatist pretensions and now renamed simply the League in a bid for national power, it today demonizes immigrants rather than Southerners. Prima gli Italiani—Italians First—was Salvini’s new slogan.

But the kids at Rialzo have not forgotten his (recent) past. "Salvini is racist against African people but also racist against people from the South," a young squatter named Roberto tells me. He points to a door painted brightly with the words "Cosenza Meticcia"—mixed, akin to the Spanish word mestizo. "Calabria is multicultural," he says. "So many peoples passed through over the centuries—Greeks, Romans, Saracens [Arabs], Normans, Spanish, Arbresh [Albanians]." Going back to ancient times, he recalls that the Bruzzi or Bruttians, the local Italic tribe, resisted Rome. "We in Cosenza inherited that mentality," he says wryly.

Battling the bureaucracy of detention

One of the murals at Rialzo depicts the local protests against the CIE—the Center for Identification and Expulsion, a prison-like camp for intercepted undocumented migrants, across the mountains to the west in the coastal city of Lamezia. It was closed in 2006 after a four-year protest campaign. A second CIE in Calabria, at Crotone, across the mountains to the east on the Ionian coast, was closed after an uprising at the camp in 2013. But there are still 10 such camps around Italy—including three in Sicily. They have recently been renamed CPRs, or Centers of Detention for Repatriation. The detained can be held at the CPRs for up to 18 months, usually followed by forced deportation.

The Italian government maintains a bureaucratic alphabet soup of agencies for every stage of processing migrants. Those deemed to have a credible case for asylum are held in a Reception Center for Asylum Seekers, or CARA. Once an asylum bid is filed and pending, the detainees are transferred to an Extraordinary Reception Center, or CAS. There are several of both in Calabria and Sicily. Those cleared as legitimate asylum applicants are released to the Protection System for Applicants, or SPRAR, with local branches often overseen by nonprofits. Those in the SPRAR system have freedom of movement and can apply for citizenship after five years.

A registered SPRAR facility in Cosenza is the Kasbah, which began as a community center in an occupied empty school building in 2001. It entered the SPRAR system in 2005, under contract to the Cosenza municipal government, with Interior Ministry oversight. The Kasbah's Emilia Corea says the center has processed hundreds of asylum applicants, helping them to find housing and providing them with counseling and other aid. Most passed through Libya, a key transit point for migrants.

Corea works with the Kasbah's multidisciplinary team for torture victims. "The big majority of those who were detained in Libya experienced torture, and that usually means sexual violence as well," she says. "And they were already fleeing violence in their home countries. In Libya, human beings are business and are tortured for extortion,” Corea relates. “If they have no money, they are forced to work or sold."

Many of those who have passed through the Kasbah were from Syria or Afghanistan, as well as conflicted or repressive African countries, such as Nigeria, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

And Corea says many of these people have been further traumatized in detention in Italy. Even at the CARA and CAS facilities, which are nowhere near as harsh as the CPRs, asylum seekers live in container housing within compounds heavily policed by the Carabinieri. "It's very hard for someone who has been tortured by soldiers, coming from war-torn countries, and then experienced more violence in transit," she says.

Worse, this system for aiding asylum seekers is to be phased out under the Salvini Decree. After the law took effect, several families were expelled onto the street from the CARA facility in Crotone—with winter approaching. "Subsidiary protection" and "humanitarian protection"—EU-recognized status afforded those who do not meet the criteria of refugee, but still have credible fear for their safety if deported to their homelands—are also to be phased out by the Salvini Decree. And under the new law, refugee status can be revoked for any crime.

Other means of legal immigration have been closing. Under the 2002 Bossi-Fini law, immigrants from outside the EU can enter only with an employment contract arranged through their embassies. Later, the Decreto Flussi (Flow Decree) imposed strict quotas on how many can enter from each country, of the kind that were imposed in the United States by the 1924 immigration law, and overturned in 1965 as a racist embarrassment.

The Interior Ministry officially provides each individual in the asylum system some 35 euros a day—but only some three euros go directly to them as pocket money. The rest goes to pay for provisioning and administration of the facility where they are being held. And Corea believes much of that is siphoned off into corruption networks. "The 'Ndrangheta operates at every level of society," she says, referring to Calabria's notorious crime machine.

Nonetheless, Salvini and the right-wing press portray the asylum-seekers as an economic drain, and competitors for jobs. "Unemployment is a problem," Corea says. "But it's not migrants who are responsible for this, but politicians. The propaganda of the media is used to create a racist climate against migrants."

From Ghana to Libya to Calabria

Translating for me in my interviews with the Prendo Casa folks is Omar Hossin, a clean-cut, reserved young man from Ghana with a pending asylum claim, now living at the Villa Savoia, one of the government buildings in Cosenza under squatter occupation. Hossin's harrowing story, related without emotion as we hang out on the Corso Mazzini, the city’s pedestrian mall, is probably all too typical.

Ghana is seen as one of the more stable countries of West Africa, but even here there are numerous agrarian conflicts that win virtually no outside media coverage. Hossin relates that in 2013, when he was 16 years old, his father was killed on the orders of what he calls a local "king." He is circumspect on the details, but apparently a land dispute was involved. There may have also been an ethnic dimension, as Hossin is of the Kotokoli people while the king (or traditional chieftain) was Ashanti—although he is not, he makes clear, speaking of the overall king of the Ashanti people in Ghana, Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II, but some lesser figure.

In any event, Hossin was sure that he was next and that he had to flee. "I felt they could find me anywhere in Ghana, and I had to get out of the country," he says. He had saved some money working as a motorcycle mechanic, and made arrangements to cross the Sahara with people-smugglers, headed for Libya, where he was told he could find work. Ten days after leaving Ghana, he arrived in Tripoli, passing through the desert as a virtual captive of the armed smugglers.

Hossin found construction work in Tripoli, and lived in an unfinished building, allowed to stay in exchange for his labor. But the sound of gunfire often kept him awake at night. This was one of the periods when rival militias were fighting for control of the city. "I was running for my life in Ghana and now there was fighting again," he says.

In July 2014, he decided to cross the Mediterranean, getting on an overcrowded boat with a group of fellow migrants and refugees—three-days passage in an uncovered outboard-motor craft not designed for the open sea. On the third day, things started to look bad. "The boat was about to sink, the motor was getting tired," Hossin recalls.

They were rescued by the Italian navy and taken to Licata, Sicily, where they were given showers and medical attention at a reception center, presumably one of the CARA facilities since closed under the Salvini Decree. "I was happy to be there with no loss of life," Hossin says.

After being screened, he was put on a chartered flight to Rome, where he was held in a camp, presumably a CAS. There were seven to a room, among some 30 at the facility. There were Italian classes, and during the day he had freedom of movement around the city. With the €2.50 daily pocket money he was given (sometimes delayed for weeks), he saved up enough to get a phone. On social media, he made a friend in Cosenza. He relocated there after his release from the camp in 2015.

With his asylum claim pending, he has been given a UN-issued passport. If his claim is accepted, he'll be able to apply for Italian citizenship in five years, based on his employment prospects. Meanwhile, he has been working on local farms, doing housework, and squatting at the Villa Savoia in a room with a gas stove but no heat or hot water.

Squatting technically puts him afoul of the Salvini Decree, which could theoretically forfeit his asylum claim. Still, he is accepting of his circumstances. "It's better than my time in Libya," he says. "I'm not afraid someone will kill me." He is sporadically in touch by phone with his mother, who is in hiding in Ghana.

Meet the New Boss?

Emilia Corea is only guardedly optimistic about the new regime in Italy, which brings together Salvini's former coalition partners, the fuzzy populists of the Five Star Movement, with the center-left Democratic Party. "Salvini is no longer the interior minister, and this is the only good news," she says. "The party that has ruled Italy with him until a month ago is still there. And more, it is going to rule the country with a party that in the past caused serious problems for people."

She recalls that it was the Democratic Party's Marco Minniti, as interior minister in 2017, who began the crackdown on NGOs operating vessels to save migrants imperiled on the Mediterranean crossing—a policy later pursued more aggressively by Salvini. It was also under the Democratic Party government that year that Italy began aiding the Libyan coast guard to intercept migrant boats, leading to a big drop in the number able to flee North Africa for Italian shores—from 180,000 in 2016 to just 23,000 last year. This policy was protested by Amnesty International as making Italy and its EU partners in the program "complicit" in the horrific abuses migrants face in Libya.

Corea sees a historical irony in the anti-immigrant atmosphere, which will clearly survive Salvini. "People don't understand that in the past Italians were in the same position as migrants today," she says. "100,000 Italians came to America because they could not live in Italy. They were subject in America to the same racist attitudes that migrants now face in Italy. But they have forgotten everything."

———

Bill Weinberg is an award-winning 30-year veteran journalist in the fields of human rights, indigenous peoples, drug policy, ecology and war. He is the author of Homage to Chiapas: The New Indigenous Struggles in Mexico (Verso, 2002), among other books. He is currently at work on a sequel about indigenous struggles in the Andean nations. He blogs daily on global politics from an anarchist perspective at CounterVortex.org

This story first appeared in the November 2019 edition of The Brooklyn Rail.

Photos by the author.

Resources:

The EU's Complicity in Migrant Abuse in Libya

Amnesty International, Dec. 18, 2017

From our Daily Report:

Calabrian connection in Brazil narco busts

CounterVortex, Sept. 18, 2019

Amnesty: EU complicit in violence against refugees

CounterVortex, March 18, 2019

UN tells migrants to leave Libya 'transit center'

CounterVortex, Dec. 13, 2019

Libya: Europe 'complicit' in horrific abuses

CounterVortex, Dec. 13, 2017

Libya slave trade becomes political football

CounterVortex, Dec. 7, 2017

Libya: Black African migrants face 'slave markets'

CounterVortex, April 17, 2017

Ghana: four killed in chieftaincy succession dispute

CounterVortex, Nov. 3, 2007

See also:

ROME SQUATTERS FACE CLAMPDOWN

by Bill Weinberg, Fifth Estate/The Villager

CounterVortex, September 2019

LEFT WAITING

Africans Caught in US-Mexico Migration Limbo

by Melisa Valenzuela, The New Humanitarian

CounterVortex, October 2019

I FOUGHT IN LIBYA

Please Don't Call Us Terrorists

by Belal Younis, Middle East Eye

CounterVortex, May 2017

—————————-

Reprinted by CounterVortex, Dec, 29, 2019

Recent Updates

1 day 26 min ago

1 day 56 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 4 hours ago