Features

WHAT NEXT FOR LIBYA?

by Mary Fitzgerald, IRIN

TRIPOLI — If any further evidence was needed of the importance of ending the power struggle that has plunged Libya into chaos since last summer, it was the reminder this week that sympathisers of the so-called Islamic State (IS) are keen to exploit the resulting power vacuum. In a January 27 attack claimed by IS, gunmen stormed a luxury Tripoli hotel popular with UN officials and diplomats, killing at least nine people, among them five foreigners. It was the deadliest in a series of incidents, which suggest that IS supporters in Libya are growing more assertive as the country's political crisis continues.

Armed groups allied to Libya's rival governments—one a militia-backed self-declared administration that took power in Tripoli after the internationally recognized government of prime minister Abdullah al-Thani fled to eastern Libya—are locked in a battle for control of the oil-rich nation.

UN officials overseeing talks in Geneva aimed at uniting the warring factions hope the hotel attack will help focus minds. It might prove "a wake-up call," said UN envoy to Libya Bernardino Léon, who argues only a unity government can tackle the IS threat. "The country is really about to collapse."

NEITHER EAST NOR WEST

How a small group of anarchists took on the Soviet Union and won!

by Bob McGlynn, Fifth Estate

With the war in Ukraine and renewed US-Russian rivalry, the need has emerged for a "neither-nor" position of the kind some anarchists and anti-authoritarians took in the Cold War—building solidarity between anti-war and left-libertarian forces on either side of the East-West divide. In this context, the US anarchist journal Fifth Estate last year ran the following look back at the ground-breaking group Neither East Nor West, which took on such work at the height of the Reagan Cold War. Neither East Nor West co-founder Bob McGlynn recounts the little-known role of this and related efforts in a period whose history has suddenly become frighteningly relevant.—World War 4 Report

During the Cold War, there was always a sector within the anarchist/left-libertarian milieu in the West that took a special interest in dissidence and repression within the Soviet Bloc. This interest was in part due to the ultra-closed nature of Soviet Bloc societies and the lack of information about opposition and activism within them that did not come from a pro-Western perspective.

This changed in 1980 with the formation of Poland's Solidarity free trade union. With a nationwide general strike and 10 million workers signing on in two to three months, Solidarity exploded Communism's frontiers. Neither East Nor West-NYC (NENW-NYC) traces its roots back to this time, when a number of anti-authoritarians in the New York City metropolitan area took advantage of Solidarity's opening. Individual activists and members of the anarcho-syndicalist Workers Solidarity Alliance, along with the (now disbanded) Revolutionary Socialist League, met while doing Solidarity support.

NIGERIAN LIVES MATTER

The Baga Massacre and the Numbers Controversy

by Obinna Anyadike, IRIN

NAIROBI — Two thousand killed or 150? Controversy surrounds the death toll in the northern Nigerian town of Baga and nearby villages following an attack in early January by the Islamist militant group Boko Haram.

BBC report on the fighting published on January 8 quoted a local government official giving a civilian death toll of as many as 2,000, although it did add that other accounts put the number in the hundreds. Amnesty International used the 2,000 figure the following day in a press release, and despite the caveats strewn through the statement, the number stuck and was taken up by the world's media. The Toronto Star did a chronology.

The government's response, some days later, was that "only" 150 people had died. The military spokesperson tweeted: "RE: @Amnesty International on Boko Haram's 'deadliest act'. They are the Evil we must all Fight not Government."

Ryan Cummings, chief of security analysis for Africa at the crisis management outfit Red24, asks: "is it credible to believe that Boko Haram had indeed killed as many as 2,000 people in a single act of mass violence?"

JIHADIST SCYLLA, IMPERIAL CHARYBDIS

Double Bind

The Muslim Right, the Anglo-American Left and Universal Human Rights

by Meredith Tax

Centre for Secular Space, New York, 2014

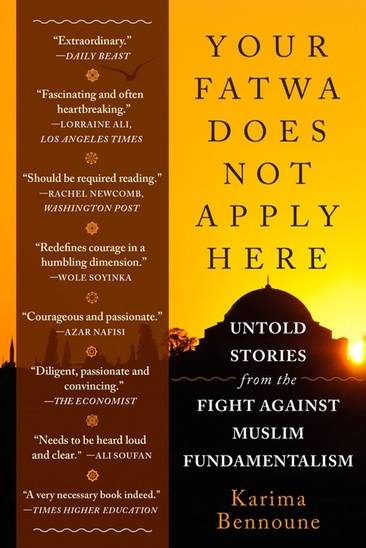

Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here

Untold Stories from the Fight Against Muslim Fundamentalism

by Karima Bennoune

WW Norton, New York, 2013

by Bill Weinberg, Dissent News Wire/Middle East Policy

Psychologist Gregory Bateson defines a "double bind" as a dilemma in which people are given conflicting sets of instructions so that obeying one means violating the other.

Meredith Tax in her brief study Double Bind (first published in the UK and now released in an American edition) explores that faced by the human rights community and progressives generally in confronting the "war on terrorism," in which Western states have committed horrific abuses in an ostensible struggle against reactionary political Islam. How do we defend the right to dissent when those being abused by the state do not recognize the right of others to dissent from their authoritarian dogmas?

PERUVIAN COMMUNITIES REJECT COP 20

Building the Movement of the People for El Buen Vivir

by Lynda Sullivan, Upside Down World

All eyes were on Peru as December began and this rising economic star hosted the United Nations Climate Change Conference or COP 20 (20th yearly session of the Conference of the Parties), the latest in the annual climate talks where 195 states congregate to discuss our changing climate. The main mission in Lima was to advance negotiations for a new climate treaty that is hoped to be agreed at the COP 21 next year in Paris.

Peru, to mark the occasion, officially labeled 2014 "The Year of the Promotion of Responsible Industry and Climate Commitment." Alongside this noble gesture, the Ollanta Humala government also passed a series of laws cutting back whatever weak environmental protection had existed and stripping the already weak Ministry of Environment of many of its key functions, in addition to laying down the red carpet in terms of tax breaks and ease of project approbation for the big investors/polluters. The economy has indeed risen in recent years as a result of this neoliberal strategy; however, so has the number of social conflicts; a report released by the Public Ombudsman's Office in September 2014 showed that on average almost 200 social conflicts are reported across the country every month, 69 percent of these conflicts being related to socio-environmental issues. In the majority of cases conflict arises when a mega-project is being forced through without consultation and against the wishes of the local population, and the resistance that naturally rises up is met with the heavy handedness of the security forces that are tasked with repressing it.

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: WHITHER JUSTICE?

from IRIN

BANGUI — As the International Criminal Court (ICC) steps up its work in the Central African Republic (CAR), pledging to bring the worst perpetrators of violence to justice, concerted efforts are being made to counter endemic impunity in CAR. But the prevailing insecurity in many parts of the country rules out any quick-fix solutions.

ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced in September that the ICC was ready to open its second investigation in CAR. According to Bensouda, a preliminary enquiry in February had "gathered and scrupulously analysed relevant information from multiple sources," leaving no doubt as to the ICC's right to intervene under the Statute of Rome. "The list of atrocities is endless," Bensouda emphasized. "I cannot ignore these alleged crimes."

The preliminaries may be out of the way now and the ICC set for a full investigation, but there has been no indication from The Hague as to how long it will take before suspects are identified, warrants issued and defendants brought to trial.

IMPRESSIONS OF ROJAVA

by Janet Biehl, ROAR Magazine

In early December an international delegation visited Cezire canton in Syria's Kurdish-majority northern region of Rojava, where they learned about the revolutionary process underway there. Longtime Vermont-based Green activist and writer Janet Biehl was part of the delegation, and offers this account. —World War 4 Report

From December 1 to 9, I had the privilege of visiting Rojava as part of a delegation of academics from Austria, Germany, Norway, Turkey, the UK, and the US. We assembled in Erbil, Iraq, on November 29 and spent the next day learning about the petrostate known as the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), with its oil politics, patronage politics, feuding parties (KDP and PUK), and apparent aspirations to emulate Dubai. We soon had enough and on Monday morning were relieved to drive to the Tigris, where we crossed the border into Syria and entered Rojava, the majority-Kurdish autonomous region of northern Syria.

IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT: ANTI-LABOR TOOL

by Steve Wishnia, Dissent News Wire

Last April, Ramón Méndez, a Mexican-born roofer in Los Angeles, complained to the Department of Labor that the contractor he worked for had stiffed him out of $12,000 he'd earned.

"Within a few days, immigration officers showed up at his house and put in a deportation order," says Cliff Smith, business manager of Roofers and Waterproofers Local 36 in Los Angeles. But Méndez was on the street nearby and saw them coming. He escaped, and with union, community, and political support, was able to make a deal. He turned himself in to the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and as he had no criminal background and the agency has a policy of staying neutral in labor disputes, he was given an "order of supervision" and later a work permit. However, says Smith, "vindictive ICE officials are requiring him to wear an ankle bracelet, making it difficult to hold steady employment to provide for his wife and four children."

Recent Updates

9 hours 35 min ago

12 hours 52 min ago

1 day 7 hours ago

1 day 8 hours ago

2 days 17 hours ago

2 days 17 hours ago

4 days 17 hours ago

5 days 7 hours ago

5 days 8 hours ago

5 days 8 hours ago