'GOING EXTINCT IS GENOCIDE'

Lakota Elders Tour to Raise Awareness About Struggle

by Victoria Law, Truthout

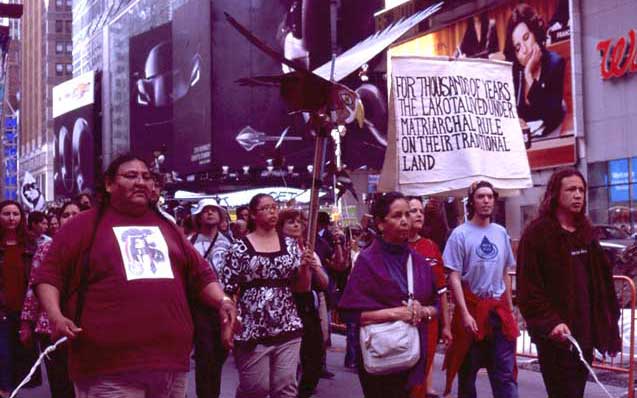

NEW YORK — On April 9, Lakota elders, activists and nonindigenous supporters marched through the streets of Manhattan to the United Nations, where they attempted to present a petition to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon. Entitled the Official Lakota Oyate Complaint of Genocide Based on the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the petition listed the numerous injustices faced by the Lakota people. (Oyate is a Sioux word for "people" or "nation.")

At the UN, security officers informed them that they would not be able to enter the building and present the complaint to the Secretary General. Instead, the security officers offered to take it to Ban's office, but refused to give the Lakota documentation verifying that their complaint had been received.

Outside the UN, Charmaine White Face, a Lakota grandmother and great-grandmother, addressed the 60 people who had marched with her. "We come here as a nation. If they won't let us take our message to them, how disrespectful is that to a nation?"

The action is part of the 13-city Truth Tour by Lakota elders and activists to draw attention to the situation of the Lakota, mobilize solidarity networks to benefit Lakota elders, and renew the Lakotas' traditional matriarchal leadership on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Reservation and across the Lakota nation. Between April 1 and 16, they traveled to Minneapolis, Chicago and other points east and west.

With Colonization Came the End to the Matriarchal Leadership

"The matriarchal system changed when the colonizers arrived in 1492," Canupa Gluha Mani, a Lakota activist and founder of the Strong Heart Warriors Society, told Truthout.

History backs up his assertion: As the United States encroached upon indigenous territory, treaties were negotiated between the United States government and the indigenous nations. After going through hundreds of documents, historians M. Annette Jaimes and Theresa Halsey asserted, "In not one of the more than 370 ratified and perhaps 300 unratified treaties negotiated by the United States with indigenous nations was the federal government willing to allow participation by native women. In none of the several thousand non-treaty agreements ... were federal representatives prepared to discuss anything at all with women. In no instance was the United States open to recognizing a female as representing her people's interests when it came to administering the reservations onto which American Indians were ultimately forced; always, men were required to do what was necessary to secure delivery of rations, argue for water rights, and all the rest." (from "American Indian Women: At the Center of Indigenous Resistance in Contemporary North America," in The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization and Resistance, ed. M. Annette Jaimes. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press, 1992, p. 322.)

White Face, a Lakota elder and great-grandmother of nine, noted that under the matriarchal system, "The ones who made the decisions for the community were the grandmothers. There were societies of grandmothers. Colonizing has forced people to forget these ways. There are still some of us who were taught the old way. I learned from my grandmother. Other people didn't have that opportunity."

More than 6,753 Lakota children have not had the opportunity to learn from their grandmothers and other elders. Among the list of injustices on the Official Lakota Oyate Complaint is the placement of Lakota children with non-Lakota foster parents. In addition, the incarceration rate for Native children is 40 percent higher than that of their white counterparts.

And there is the matter of language. "In one lifetime, the number of Lakota speakers has dropped 75 percent," states the Complaint. "There have been no new Lakota speakers in three generations. There are 6,000 to 8,000 Lakota language speakers left."

Other realities faced by the Lakota living on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Reservation include:

- An average life expectancy of 44 years

- An infant mortality rate more than 300 percent the national average

- Alcoholism affecting eight in ten families

- A tuberculosis rate on Lakota reservations approximately 800 percent higher than the national average

- A cervical cancer rate 500 percent higher than the national average

- Corruption in the current leadership

- Retaliation against elders and activists who attempt to speak out against the corruption

White Face notes that she and other Lakota grandmothers seek the enforcement of the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty. In the treaty, the United States recognized the Black Hills of Dakota as part of the great Sioux Reservation and set the land aside for exclusive use by the Sioux people. However, six years later, Gen. George Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills, where they found gold. Miners began moving into Sioux territory, demanding protection from the US army. In 1876, Custer led an army detachment to the Little Bighorn River, where they were soundly defeated by the Sioux. The following year, the US government confiscated the land from the Sioux.

In 1882, the United States began imposing an assimilation policy on the Lakota and other Native nations, outlawing key spiritual practices and forcibly removing children from their homes to send them to boarding schools, where thousands died or ran away. In 1890, at what would become known as the massacre at Wounded Knee, government forces killed over 300 Lakota men, women and children.

"The [1868] treaty spells out absolute and undisturbed land use and occupation" for the Lakota, White Face told Truthout. "If we could get that, we can fix everything else our way."

She noted that the Lakota have been sending delegates to the UN since 1984 requesting its assistance in helping enforce the terms of the Fort Laramie treaty. "We've never been able to get them to help."

Corruption Within

Corruption in the local leadership has plagued the people on Pine Ridge. In the 1970s, allegations of corruption of Pine Ridge's tribal council helped instigate the takeover of Pine Ridge's Wounded Knee by the American Indian Movement and a 71-day siege by federal forces. Pine Ridge is today, and was then, one of the poorest areas in the United States.

Gluha Mani recounted a meeting two months before the tour began. "They almost beat Charmaine White Face up. Why? Because she was telling the truth! Someone had to come get me to protect her."

When asked about being attacked at a meeting, White Face responded, "Which one?" Then, more soberly, she stated, "When I speak out against corruption, that's when I get attacked."

One week before the Truth Tour left South Dakota, another Lakota woman, Lorraine White Face, was assaulted while buying gas. "She was assaulted because she challenged the tribal council. She told the head of the tribal council to do his job professionally or not at all," recalled Gluha Mani, whom she called from a nearby store.

Barbara Charging Crow does not live on Pine Ridge. Her husband's mother is one of the Lakota elders in Wanblee, South Dakota, east of Pine Ridge. However, corruption is just as much a problem there as on Pine Ridge and other reservations.

Charging Crow told Truthout that in the summer of 2010, the government began laying water pipes through Wanblee, diverting the area's groundwater and replacing it with water from the Missouri River. "My mother-in-law used to be able to turn on her faucet and get water from all over. It smelled a certain way; it tasted a certain way. And then, in summer 2010, she turns on her tap and gets water that smells different and tastes different and is polluted river water. And the whole time, church groups are there, patting kids on the head, cleaning up the garbage, singing songs about Jesus Christ, and the whole time the government's trenching our water.

"The government sent $6 million, supposedly for 'economic support,'" Charging Crow continued. "The cover page said it was for economic support. But under the first page, it said that this was to pay for our water. Right away, 60 percent of that money is unaccounted for. The behavior of embezzlement has been going on for so long that people think they can get away with more and more. It's getting worse. Then, just before the grandmas leave, people start getting checks for $1,000 for the change in their water. Is $1,000 going to cover people's cancer treatment?"

When Charging Crow heard about the Truth Tour and learned that some of the grandmothers were unable to travel, she decided to join. "I'm also a grandma," she said. "I'm a young grandma, not an old one. I'm not an 80-year-old grandma. But I wanted to raise awareness of the abuses and the need for accountability. These grandmas have been living here this whole time, but now they're looking at real-life extinction."

Treaty Territories Surrounded by Open Uranium Mines

Charmaine White Face is the spokesperson for the treaty council created in 1894 to work toward the enforcement of the Fort Laramie treaty. She is also a biologist concerned about the environment of the treaty territory. In the fall of 2003, White Face learned about the uranium mines on the Lakota lands abandoned in the 1970s. Many of the mines have no barriers or signs warning the public not to enter. Many are still emitting radiation. In response, she started Defenders of the Black Hills, an all-volunteer group that pushes for the clean-up of abandoned uranium mines on sacred Lakota Lands. White Face has taken journalists into the mines to see the dangers firsthand. "You'll see front-page exposés of the uranium mines in [news outlets] in Germany, but not here," she added.

Currently, the group is seeking a sponsor for a federal bill appropriating enough funds for the immediate cleanup of all abandoned uranium mines in the region and assistance to those harmed by radiation. Charmaine White Face cites the example of the Riley Pass Mine, which had been bought by chemical manufacturer Tronox Incorporated. Tronox filed for bankruptcy. Although the bankruptcy settlement agreement includes a $96,000 payment to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the Riley Pass Mine, White Face stated that no cleanup has occurred. Instead, a sign has been posted warning people not to enter the area.

Charmaine White Face and other defenders of the Black Hills remain undeterred. She notes that even the most assimilated (or "colonized," as she calls them) people on Pine Ridge support her efforts to clean up the uranium mines. In 2007, White Face won the Nuclear-Free Feature Award for her work in exposing the dangers of uranium mining.

The Truth Tour

The Lakota elders did not gain entrance to the UN that Tuesday afternoon. (As of thenight of April 10 - the day following their appearance at the UN's Manhattan headquarters - they were still waiting for word from the secretary general's office.)

That night, they screened their documentary Red Cry and spoke about the issues at New York's Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew. "Our reception in New York has been exceptional and overwhelming,"Charmaine? White Face told Truthout the following day.

Charging Crow agrees. "All the people everywhere have been beautiful. Meeting other activists and organizers who have done so many amazing things is an incredibly humbling experience." But she reminds us, "We are trying to get people to see the ugly realities of extinction and genocide. These grandmas have been living here [in Pine Ridge, Wanblee and other territories] this whole time, but now they're looking at real-life extinction. Going extinct is genocide.

———

This article first appeared April 22 on Truthout.

Copyright, Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission.

From our Daily Report:

Cornhuskers pack Keystone XL hearing

World War 4 Report, Dec. 7, 2012

Lakota oppose expansion of uranium operations

World War 4 Report, Jan. 27, 2008

—————————-

Reprinted by World War 4 Report, May 5, 2013

Recent Updates

1 day 14 hours ago

2 days 3 hours ago

2 days 4 hours ago

2 days 4 hours ago

2 days 10 hours ago

2 days 10 hours ago

2 days 13 hours ago

2 days 13 hours ago

2 days 13 hours ago

2 days 13 hours ago